I don’t actually hate best practices, of course. But I’ve googled “I hate best practices.” More than once. So I feel like other people must be googling it, too. Therefore, it’s a good title for this post, for two reasons:

I clearly feel some type of way about best practices, and that type of way is not “love.”

SEO.

If you do creative work in the ad industry, you know what best practices are, because the client, your boss, or the account team emailed some over this morning. (Please confirm receipt.) Best practices are the way you’re supposed to do things. When they plop into your inbox with all the subtlety of a plate of eggs hitting the counter at Waffle House, you’re on deadline, and have 27,000 other things going on, and the last thing you want to do is reinvent the wheel and slow the process down for everybody. Sure, some of the best practices may seem a little “off” to you. Maybe one or two of them look like, let’s say, literally the opposite of what you might call “a good idea.” But who are you to ask questions? You just got out of a company-wide training session about the importance of “being a team player.” And you have tickets to see the Magnetic Fields at City Winery at 8. So you sigh, bow your head, and defer to the best practices.

Don’t do that.

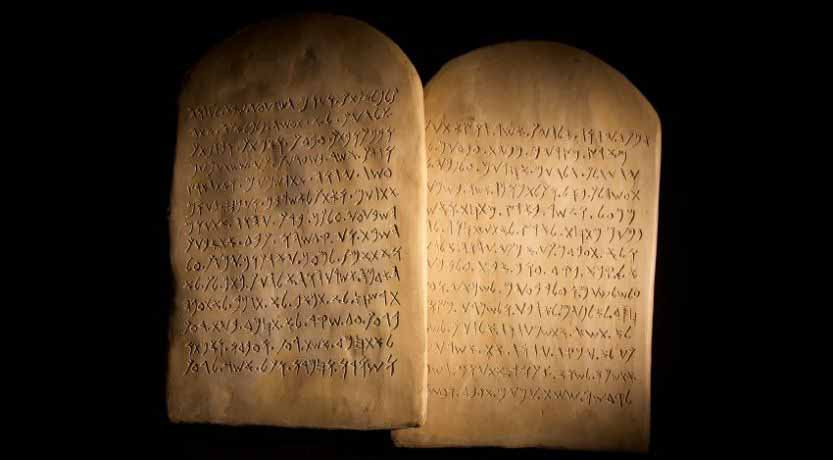

Questioning authority can be scary. Especially if that authority has a name as unquestionable as “best practices.” These aren’t just good practices. They’re the best. That sacred appellation instills a reverence previously reserved for the Ten Commandments. (Which, by the way, I have a few notes on, if Anyone’s listening. The “graven images” thing — can we cut that? If we still need a total of ten because of all the equity that the brand has built over the years, I have some suggestions for a replacement. How would the client feel about “No Watching Videos On The Bus With The Sound On?” I can wordsmith it.)

So I understand the impulse to quietly obey the best practices, even if they contradict every shred of creative judgement you have. But I would urge you, next time you get instructed to do something that you feel is a mistake, to simply not do that thing. Don’t be a jerk about it, of course. Provide rationale. Be nice. Advocate for your position in a respectful, persuasive way. The client may say “do it anyway,” and you may have to do it anyway. But at least give them the chance to let you do what they’re purportedly paying you for, which is, may I remind you, being a creative, thoughtful person who brings your talent, experience, and perspective to the table.

I’m not saying that you should reflexively disregard any wisdom anyone ever tries to share with you. A lot of people have a lot of experience, and many of them have smart advice that bears consideration. (Case in point, a certain guy who has two thumbs.)

My point is simply this: Best practices shouldn’t be the end of the conversation. They should be the start of it. Here’s the middle of the conversation: Who came up with these “best practices?” When? Has anything changed in the media landscape since then? (That’s an easy one, because the answer is always yes.) Is it possible that the thing you’re working on has particular considerations that were not included when the “best practices” were conceived? Because maybe, just maybe, it’s time to reevaluate them. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Facebook’s “Video Best Practices Checklist” currently says:

It’s a myth that only short videos work well on Facebook. In fact, both short and longer videos can resonate, as long as the length makes sense for your content and keeps fans coming back for more.

Now they tell us. It’s a myth! And yet, I’m pretty sure that I’ve been lectured on “Facebook video best practices” about eleventy-thousand times, and every time a central principle was that they needed to be short enough that unwilling viewers would be subjected to the whole video before they could desperately scroll past it. What happened? Who was responsible for weaving this narrative, this lie, this myth? Was it Facebook itself? Were they wrong? Or were they right then, but things changed?

Perhaps we’ll never know. But we do know this: best practices aren’t set in stone. The Facebook video best practices were one thing, and then somebody questioned them, and now they’re a myth that you were foolish enough to believe! How silly of you! (Don’t you love how they made it your fault?)

I’m old enough to remember when video games used to come with paper manuals. At the end of the manuals there would sometimes be a page of “tips & tricks.” I like that phrase. It’s casual. It implies that you can use the tips and tricks, or not, as you see fit, depending on the situation. It feels like it’s inviting you to play the game, and maybe discover your own tips and tricks that even the game designers hadn’t thought of. Maybe yours might even be better. “Tips & tricks” acknowledges the full spectrum of life’s infinite shades of nuance, as opposed to the unyielding, religious dogma of “best practices.”

The ad industry will never stop using the phrase “best practices,” because everyone wants to wear a full suit of medieval plate armor that says “I Know What I’m Doing, Don’t Question Me.” But I encourage you, next time you’re faced with a stone tablet of instructions from some self-appointed Moses with an M.B.A., to mentally label it “tips & tricks.” Then, if the spirit moves you, suggest some edits.